Take a Walk Down Tokaido Road

In today’s world, it takes someone roughly five and a half hours to travel 514 kilometers, or 320 miles by car. In the 1600s, it took two to three weeks to travel the same distance by foot, cart or animal. Because a journey of this magnitude spanned days and not hours, it was logical to have more than just a simple rest stop for travelers to get some food, stretch their legs or use the bathroom.

In today’s world, it takes someone roughly five and a half hours to travel 514 kilometers, or 320 miles by car. In the 1600s, it took two to three weeks to travel the same distance by foot, cart or animal. Because a journey of this magnitude spanned days and not hours, it was logical to have more than just a simple rest stop for travelers to get some food, stretch their legs or use the bathroom.

When Tokugawa Iyeyasu, later known as one of the “Great Unifiers” of Japan, came to power in 1603, he decreed that the Japanese feudal lords, or daimyos, should make an annual visit to his seat of power at Edo (present-day Tokyo). With all the pomp and circumstance of their class, the daimyos would often travel in large entourages, both to display their wealth and power and for protection. Due to the size of these caravans, a road accommodating this processional became one of the most well-traveled highways in Japanese history. The Tokaido Road extended 514 kilometers from the Nihonbashi Bridge in Edo to the Great Sanjo Bridge in Kyoto. Along the route were inns, restaurants, marketplaces and other establishments, as well as local villages. Over time, 53 recognized stops, or stages, offered travelers places to eat, rest, trade, and take in spectacular views of the island and surrounding waterways. This road, however, was not just a highway for the elite. Locals taking their goods to market, peddlers from various parts of the island, other traveling parties and others used it, too.

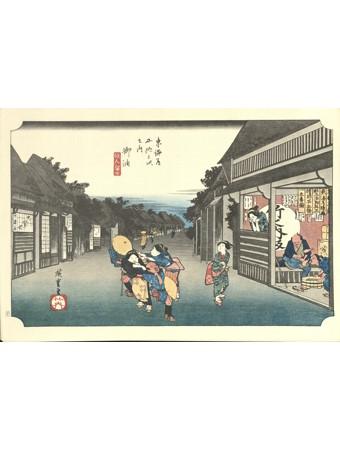

Over 200 years later, the master artist Hiroshige (1797-1858) captured the essence of the Tokaido Road as well as its 53 stages, the inhabitants at each stop, and the magnificent landscapes in his woodblock prints, “The Fifty-Three Stages of Tokaido.” A leading artist of his time, Hiroshige created 55 color woodblock prints to memorialize the historic road and the world around it. Not only are these prints beautiful works of art, but they also document what life was like during Japan’s Edo period. Scenes of traders selling their goods, ladies in kimonos walking the streets, fishermen by the river and farmers in their fields describe everyday life in Japan. Landscapes magnify the vastness and rurality of the time before any form of modernization or industrialization touched the Japanese shores.

Students in HIST 363, Japanese Civilizations, view “The Fifty-Three Stages of Tokaido,” during their visits to the Nabb Research Center. From the collection of prints, they can study the economics, transportation, religion, gender roles, hospitality industry and other infrastructures of the 17th, 18th and 19th century. Rather than reading text on a page, they can visualize the world of Edo Japan.

Students in ART 336, History of Graphic Design, study the intricate details of the prints. To make color prints in this Ukiyo-e style, Hiroshige would have first drawn a sketch of his intended piece. Then he would have worked with an engraver and printer to carve wooden blocks for each color in the print. The blocks would then be inked with their intended color, and pressed to paper, creating a layered and complete image.

This collaborative and complex form of art, especially when the subject matter strays from the normal courtesans and Kabuki actors 1, is a unique and exciting piece within the Nabb Center’s Special Collections. “The Fifty-Three Stages of Tokaido” is available for research by students, art enthusiasts and the curious mind. Satisfy your wanderlust by stepping out of your house and onto the Tokaido Road.

1 Department of Asian Art. “Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2003)